Helping Students Understand the Law at University of Arizona

- Location

- Arizona

- Size

- 100+

- Use case

- Higher Education

U of A professor pinpoints misunderstandings with multiple choice polls.

Teaching the Intricacies of the Law

Christopher Robertson, who teaches at University of Arizona’s James. E. Rogers College of Law, uses multiple-choice polling to minimize those misunderstandings and create more informed students. Robertson teaches first-year law students at Arizona University’s James. E. Rogers College of Law.

“Law students can easily go an entire semester passively attending class and both the professor and student discover on the final exam that they have not grasped the concepts covered in class. I find that polling in class encourages active student participation and uncover misunderstanding of how to apply the law that warrant a second look.” ~The Method: Cascading Persuasion

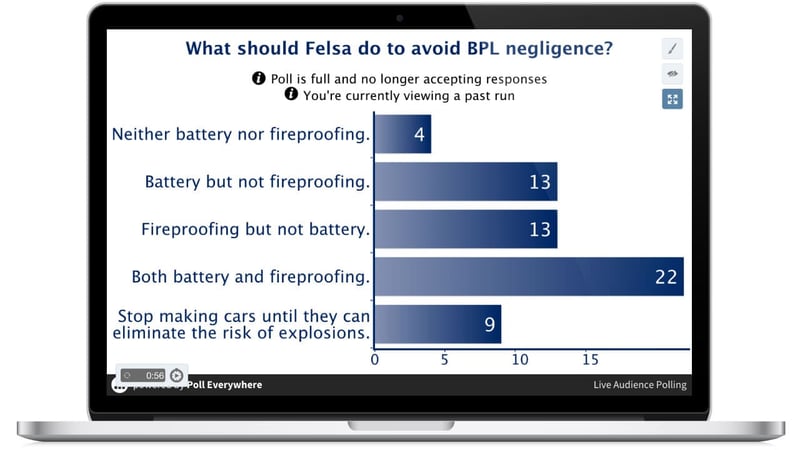

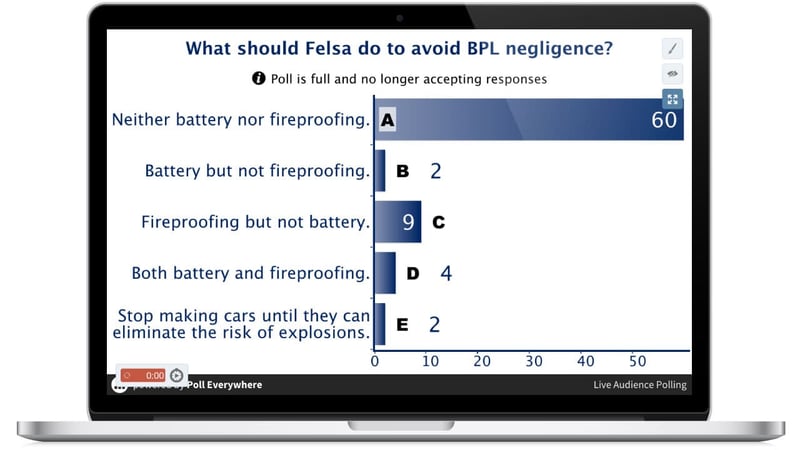

After Robertson’s class has spent some time discussing a particular aspect of a new case, Chris uses a capstone session to gauge student understanding of the covered concepts.

The capstone class (sometimes inspired by real-life events) utilizes several multiple-choice questions that each have a correct answer, which is clear to a student that understands the law but difficult to guess for those that don’t. At the start of the class, students read the details of the case, then answer the related questions in the poll.

If a significant portion of the students get the answer wrong, Robertson instructs each student to turn to the student next to him or her. Their task: to persuade their fellow classmate that their answer is correct. Often, students pull out the relevant texts, and dissect the rule together. Disagreements can be heated, but students also develop professional skills of argumentation. When the two reach a consensus, they move onto another classmate to plead their case.

Results

The consensus then cascades through the class, and students usually reach a class-wide consensus in just a few minutes—and their collective answer is usually correct.

If the consensus fails, Chris often finds that it’s because of a slight misunderstanding about the nuances of the choices. In those cases, it’s easy to correct the mistake.

Other times, the misunderstanding is in the law itself, and Robertson knows exactly which material needs to be covered in more detail.

Wrapup

Despite using anonymous polling—or perhaps because of it—Robertson usually sees engagement levels of about 90 percent in his polling. Students love the capstone class, and never fail to mention that they look forward to each session in their teacher evaluations.

Better engagement leads to better understanding, but the benefits apply to Chris, too: he can use the results of the polling to improve his methods for future classes, making sure the same misunderstandings don’t occur twice. This leaves more time to delve deeper and reach the most interesting parts of the material.

How can you do this?

Step 1

Create a multiple choice poll by clicking “Create poll,” typing in your question, and choosing the “multiple choice” format.

Step 2

Type your response options (you can also use images as responses) and click “create.”

Step 3

Students can choose how they’d like to respond: texting or via the web.

Step 4

When responses are mostly correct, simply explain the case quickly to the few remaining confused, and move on. You may or may not choose to let students view responses. Chris prefers not, so that students aren’t tempted to herd with the majority. If not, you can follow along on your own phone, tablet, or computer.

Step 5

If responses aren’t correct, review the material until you’re satisfied.

Poll Everywhere for learning and development

Power your next professional development training with live audience feedback.